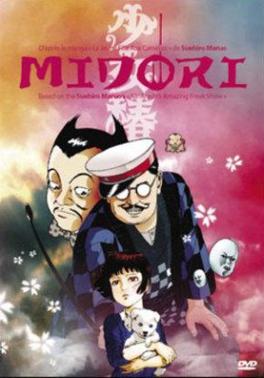

After her

mother’s untimely death, the orphan girl Midori seeks refuge with a gang of

deformed circus freaks. Her everyday life in the circus turns out to be a

living hell: the abandoned girl has to do the dirty work for the sideshow

attractions, who humiliate, strike and sexually abuse her. As a midget magician

enters the group and falls in love with young Midori, the circumstances rapidly

change for the better. However, new trouble is already brewing and Midori’s

peaceful life is at peril.

“Midori –

Shôjo Tsubaki” is adapted from “Mr Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show”, a manga comic

by prolific illustrator Suehiro Maruo. Maruo, who has also created similar manga,

such as “Ultra-Gash Inferno” and “The Laughing Vampire”, is seen as one of the

most famous artists in the field of “Ero Guro”. This Japanese art style is

known for its drastic depiction of decadent conduct, eroticism (oftentimes bordering

on the pornographic), violence and (sexual) sadism. There is no doubt that

Maruo’s art incorporates all of these aspects: his manga is gory, some would

say downright perverted and highly surreal and expressionistic in its approach.

Especially the latter defines his work and distinguishes it from the majority

of dull hentai manga. When it comes to these qualities, “Mr. Arashi’s Amazing

Freak Show” is certainly no exception, many fans even see it as the highlight

of Maruo’s flawless bibliography. And yes, all of Maruo’s trademark ingredients

are there and harmonize with each other perfectly, therefore it comes to no

surprise that Hiroshi Harada chose to make a film out of it. Haranda underwent

this painstaking procedure virtually on his own and all of the funds came out

of his own pocket. One thing can be said for sure: the final result is very

unorthodox and even encountered some troubles with censorship in its homeland

Japan, which is usually known for allowing all kinds of atrocious films. But is

his adaption worthy of the manga?

“Midori –

Shôjo Tsubaki” is adapted from “Mr Arashi’s Amazing Freak Show”, a manga comic

by prolific illustrator Suehiro Maruo. Maruo, who has also created similar manga,

such as “Ultra-Gash Inferno” and “The Laughing Vampire”, is seen as one of the

most famous artists in the field of “Ero Guro”. This Japanese art style is

known for its drastic depiction of decadent conduct, eroticism (oftentimes bordering

on the pornographic), violence and (sexual) sadism. There is no doubt that

Maruo’s art incorporates all of these aspects: his manga is gory, some would

say downright perverted and highly surreal and expressionistic in its approach.

Especially the latter defines his work and distinguishes it from the majority

of dull hentai manga. When it comes to these qualities, “Mr. Arashi’s Amazing

Freak Show” is certainly no exception, many fans even see it as the highlight

of Maruo’s flawless bibliography. And yes, all of Maruo’s trademark ingredients

are there and harmonize with each other perfectly, therefore it comes to no

surprise that Hiroshi Harada chose to make a film out of it. Haranda underwent

this painstaking procedure virtually on his own and all of the funds came out

of his own pocket. One thing can be said for sure: the final result is very

unorthodox and even encountered some troubles with censorship in its homeland

Japan, which is usually known for allowing all kinds of atrocious films. But is

his adaption worthy of the manga? The story

of young Midori is certainly a gruesome one. At the beginning of the film, she

is introduced as a virtuous, poor girl who is forced to walk the streets

selling flowers in order to be able to pay for a school trip. After having

arrived back home, she notices that her mother has died and rats have already

started eating her. Her stay with the circus people starts only a few moments

later. From the first moment on, the film makes it abundantly clear that Midori

is a tragic heroine, whose suffering will go on throughout the whole film. She

assumes a kind of Cinderella-esque position, in which she is constantly exploited,

beaten and abused sexually by the sideshow freaks, who are the exact opposite

of the kind-hearted and beautiful girl. They are mean, violently sadistic and

perverted. Maruo seems to have put a lot of thought into the character designs.

The snake woman, the “worm”, the freak with the crooked limbs as well as the

amputee, their designs are all extremely interesting and their appearance is literally

obnoxious. The contrast is visible in every second: one very powerful scene, in

which Midori is forced to wash the worm and the crooked freak, lets the

audience relive her disgust in every possible way.

The story

of young Midori is certainly a gruesome one. At the beginning of the film, she

is introduced as a virtuous, poor girl who is forced to walk the streets

selling flowers in order to be able to pay for a school trip. After having

arrived back home, she notices that her mother has died and rats have already

started eating her. Her stay with the circus people starts only a few moments

later. From the first moment on, the film makes it abundantly clear that Midori

is a tragic heroine, whose suffering will go on throughout the whole film. She

assumes a kind of Cinderella-esque position, in which she is constantly exploited,

beaten and abused sexually by the sideshow freaks, who are the exact opposite

of the kind-hearted and beautiful girl. They are mean, violently sadistic and

perverted. Maruo seems to have put a lot of thought into the character designs.

The snake woman, the “worm”, the freak with the crooked limbs as well as the

amputee, their designs are all extremely interesting and their appearance is literally

obnoxious. The contrast is visible in every second: one very powerful scene, in

which Midori is forced to wash the worm and the crooked freak, lets the

audience relive her disgust in every possible way. Furthermore,

Midori gets stripped, whipped, kicked and struck on various occasions. The

image of the whip-wielding circus director is a perfect example for the manner

in which violence and despotism are combined in “Midori”. The idea of the

victimized, righteous heroine is certainly one that has been used in various

films, literature etc (for example Sade’s “Justine”), but within this context

it shines in new splendour. This is not only due to the subtle hints at fascist

imagery found in the scenes depicting abuse and humiliation, but also because

of the constant back and forth between vile, disgusting scenes and highly

aesthetic ones. Especially the combination of sex and violence plays a plays a

huge role when it comes to the effect this film has. The ménage-à-trois between

the amputee, the muscular man and the snake woman, the licking of a young girls

eyeball during sex and the amputated villain raping Midori, all these scenes

are terribly gruesome but somehow still magnificent at the same time. However,

the “pure” violence shown in some scenes, for example the slaughtering of puppies

or asphyxiation with dirt, are still pretty direct and hard.

Furthermore,

Midori gets stripped, whipped, kicked and struck on various occasions. The

image of the whip-wielding circus director is a perfect example for the manner

in which violence and despotism are combined in “Midori”. The idea of the

victimized, righteous heroine is certainly one that has been used in various

films, literature etc (for example Sade’s “Justine”), but within this context

it shines in new splendour. This is not only due to the subtle hints at fascist

imagery found in the scenes depicting abuse and humiliation, but also because

of the constant back and forth between vile, disgusting scenes and highly

aesthetic ones. Especially the combination of sex and violence plays a plays a

huge role when it comes to the effect this film has. The ménage-à-trois between

the amputee, the muscular man and the snake woman, the licking of a young girls

eyeball during sex and the amputated villain raping Midori, all these scenes

are terribly gruesome but somehow still magnificent at the same time. However,

the “pure” violence shown in some scenes, for example the slaughtering of puppies

or asphyxiation with dirt, are still pretty direct and hard.

“Midori”’s

visuals owe much to the expressionist art of the 1920s. The circus, as well as

some camera angles and landscapes, are reminiscent of “The Cabinet of Dr.

Caligari”, the circus people made me recall “Todd Browning’s ‘Freaks’”. Although

the whole film is accompanied by a touch of macabre luridness, there are still

scenes which are nothing short of gorgeous. The entanglement between our

heroine and the midget is told in picturesque, almost fantasy-like imagery. Our

couple walks through moonlit alleys and marvelous snowstorms, accompanied by

romantic music. Another scene shows Midori walking through enormous drapes and

into flickering black and white recordings out of her own memory. “Midori” has a

hell of a lot to offer besides sleaze and gore. Be that as it may, an aura of

sickness is always to be found and in its presence, beauty and ugliness become

one and form an impressive work of art, which entices and disgusts you at the

same time. This ambivalence gives birth to some awesome parts. One of the most

spectacular scenes shows the magician wreaking havoc on a crowd of people,

making their faces split up in two, exploding their bellies, ripping out their

extremities and so on. There is only one word to describe all of this:

phenomenal.

When

talking about stylistic devices, there are many features worth mentioning.

Oftentimes, director Harada will only show still images in which only the

mouths move (sometimes not even that). Therefore, the animation in some parts

can’t be seen as too well, but this gives Maruo’s perfectly constructed

pictures the chance to unfold their power to their full extent. Furthermore,

many actions are depicted in a bizarre and completely surreal way: for example,

Midori’s rape is staged using a frozen image drenched in red, which only shows

her contorted face buried under the

amputees swirling bandages, whereas the freaks are introduced to the viewer by

hasty, fast cut stills accompanied by loud commentary. These are the moments where

the expressionist/surreal vibe proves to be truly superior and one gets the

feeling that “Midori” is nothing less than a marginally animated work of art

and not an anime. For the average anime fan this may be a flaw, but taking

Suehiro Maruo’s manga into account, there is no doubt that this was the right

decision. In contrast to this exaggerated way of portraying intense scenes, childhood

memories and harmonious thoughts are shown in soft, childlike imagery. Once again,

the two opposites interact beautifully.

Conclusion:

“Midori” is quite special. Varying, downright brilliant when it comes to style

and highly gruesome, this is a very rare, long forgotten gem. “Midori” works in

other dimensions than your classic anime and can be recommended to every fan of

remote art. Harada’s adaptation is rich in detail and a work of love. Each

viewer has to decide, whether the manga or the anime is the better choice and

whether or not they can be interchanged. However, both are strongly

recommended to just about anyone.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen